- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 100000 ریال باشد .

توجه : جهت برخورداری از مزایای در نظر گرفته شده برای مشتریان لطفا ثبت نام نمائید.

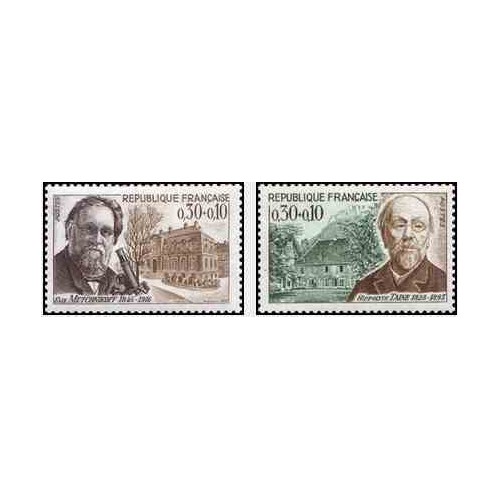

| Élie Metchnikoff | |

|---|---|

Élie Metchnikoff, c. 1908

|

|

| Born | Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov 15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1845 Ivanovka, Kharkov Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 15 July 1916 (aged 71) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | Odessa University University of St. Petersburg Pasteur Institute |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for | Phagocytosis cell-mediated immunity gerontology |

| Notable awards | Copley Medal (1906) Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1908) Albert Medal (1916) |

Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (Russian: Илья́ Ильи́ч Ме́чников, also written as Élie Metchnikoff) (15 May [O.S. 3 May] 1845 – 15 July 1916) was a Russian zoologist best known for his pioneering research in immunology.[1][2][3]

In particular, he is credited with the discovery of phagocytes (macrophages) in 1882. This discovery turned out to be the major defence mechanism in innate immunity.[4] He and Paul Ehrlich were jointly awarded the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "in recognition of their work on immunity".[5] He is also credited by some sources with coining the term gerontology in 1903, for the emerging study of aging and longevity.[6][7] He established the concept of cell-mediated immunity, while Ehrlich that of humoral immunity. Their works are regarded as the foundation of the science of immunology.[8] In immunology, he is given an epithet the "father of natural immunity".[9]

Mechnikov was born in the village Ivanovka, near Kharkov, now Kupiansk Raion, Ukraine. He was the youngest of five children of Ilya Ivanovich Mechnikov, a Russian officer of the Imperial Guard.[3] His mother, Emilia Lvovna (Nevakhovich), the daughter of the Jewish writer Leo Nevakhovich, largely influenced him on his education, especially in science.[10][11] The family name Mechnikov is a translation from Romanian, since his father was a descendant of the Chancellor Yuri Stefanovich, the grandson of Nicolae Milescu. The word "mech" is a Russian translation of the Romanian "spadă" (sword), which originated with Spătar. His elder brother Lev became a prominent geographer and sociologist.[12]

He entered Kharkov Lycée in 1856 where he developed his interest in biology. Convinced by his mother to study natural sciences instead of medicine, in 1862 he tried to study biology at the University of Würzburg, but the German academic session would not start by the end of the year. So he enrolled at Kharkov University for natural sciences, completing his four-year degree in two years. In 1864 he went to Germany to study marine fauna on the small North Sea island of Heligoland. He was advised by the botanist Ferdinand Cohn to work with Rudolf Leuckart at the University of Giessen. It was in Leuckart’s laboratory that he made his first scientific discovery of alternation of generations (sexual and asexual) in nematodes. and then at Munich Academy. In 1865, while at Giessen, he discovered intracellular digestion in flatworm, and this study influenced his later works. Moving to Naples the next year he worked on a doctoral thesis on the embryonic development of the cuttle-fish Sepiola and the crustacean Nelalia. A cholera epidemic in the autumn of 1865 made him move to the University of Göttingen, where he worked briefly with W. M. Keferstein and Jakob Henle. In 1867 he returned to Russia to get his doctorate with Alexander Kovalevsky from the University of St. Petersburg. Together they won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize for their theses on the development of germ layers in invertebrate embryos. Mechnikov was appointed docent at the newly established Imperial Novorossiya University (now Odessa University). Only twenty-two years of age, he was younger than his students. After involving in a conflict with senior colleague over attending scientific meeting, in 1868 he transferred to the University of St. Petersburg, where he experienced a worse professional environment. In 1870 he returned to Odessa to take up the appointment of Titular Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy.[3][10]

In 1882 he resigned from Odessa University due to political turmoils after the assassination of Alexander II. He went to Messina to set up his private laboratory. He returned to Odessa as director of an institute set up to carry out Louis Pasteur's vaccine against rabies, but due to some difficulties left in 1888 and went to Paris to seek Pasteur's advice. Pasteur gave him an appointment at the Pasteur Institute, where he remained for the rest of his life.[3]

Mechnikov became interested in the study of microbes, and especially the immune system. At Messina he discovered phagocytosis after experimenting on the larvae of starfish. In 1882 he first demonstrated the process when he pinned small thorns into starfish larvae, and he found unusual cells surrounding the thorns. The thorns were from a tangerine tree made into a Christmas tree. He realized that in animals which have blood, the white blood cells gather at the site of inflammation, and he hypothesised that this could be the process by which bacteria were attacked and killed by the white blood cells. He discussed his hypothesis with Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Claus, Professor of Zoology at the University of Vienna, who suggested to him the term "phagocyte" for a cell which can surround and kill pathogens. He delivered his findings at Odessa University in 1883.[3]

His theory, that certain white blood cells could engulf and destroy harmful bodies such as bacteria, met with scepticism from leading specialists including Louis Pasteur, Behring and others. At the time, most bacteriologists believed that white blood cells ingested pathogens and then spread them further through the body. His major supporter was Rudolf Virchow, who published his research in his Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin (now called the Virchows Archiv).[10] His discovery of these phagocytes ultimately won him the Nobel Prize in 1908. He worked with Émile Roux on calomel, an ointment to prevent people from contracting syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease.[5]

In 1887, he observed that leukocytes isolated from the blood of various animals were attracted towards certain bacteria.[13] This attraction was soon proposed to be due to soluble elements released by the bacteria [14] (see Harris[15] for a review of this area up to 1953). Some 85 years after this seminal observation, laboratory studies showed that these elements were low molecular weight (between 150 and 1500 Dalton (unit)s) N-formylated oligopeptides, including the most prominent member of this group, N-Formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine, that are made by a variety of growing gram positive bacteria and gram negative bacteria.[16][17][18][19] Mechnikov's early observation, then, was the foundation for studies that defined a critical mechanism by which bacteria attract leukocytes to initiate and direct the innate immune response of acute inflammation to sites of host invasion by pathogens.

Mechnikov also developed a theory that aging is caused by toxic bacteria in the gut and that lactic acid could prolong life. Based on this theory, he drank sour milk every day. He wrote The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies, in which he espoused the potential life-lengthening properties of lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus).[20][21] He attributed the longevity of Bulgarian peasants to their yogurt consumption.[22]

Mechnikov died in 1916 in Paris from heart failure.[23]

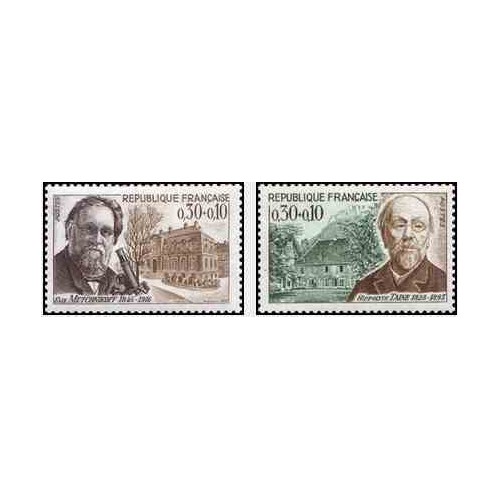

| Hippolyte Taine | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Hippolyte Taine by Léon Bonnat.

|

|

| Born | Hippolyte Adolphe Taine April 21, 1828 Vouziers, France |

| Died | March 5, 1893 (aged 64) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Signature |  |

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (21 April 1828 – 5 March 1893) was a French critic and historian. He was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. Literary historicism as a critical movement has been said to originate with him.[1] Taine is particularly remembered for his three-pronged approach to the contextual study of a work of art, based on the aspects of what he called "race, milieu, and moment".

Taine had a profound effect on French literature; the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica asserted that "the tone which pervades the works of Zola, Bourget and Maupassant can be immediately attributed to the influence we call Taine's."[2]

The tomb of Hippolyte Taine is in Roc de Chère National Nature Reserve, in Talloires, near the Lake Annecy.

Taine was born in Vouziers,[3] but entered a boarding school, the Institution Mathé, whose classes were conducted at the Collège Bourbon, at the age of 13 in 1841, after the death of his father.[4] He excelled as a student, receiving a number of prizes in both scientific and humanistic subjects, and taking two Baccalauréat degrees at the École Normale before he was 20.[5] Taine's contrarian politics led to difficulties keeping teaching posts,[6] and his early academic career was decidedly mixed; he failed the exam for the national Concours d'Agrégation in 1851.[7] After his dissertation on sensation was rejected, he abandoned his studies in the social sciences, feeling that literature was safer.[8] He completed a doctorate at the Sorbonne in 1853, with considerably more success in his new field; his dissertation, Essai sur les fables de La Fontaine, won him a prize from the Académie française.[9]

Taine was criticized, in his own time and after, by both conservatives and liberals; his politics were idiosyncratic, but had a consistent streak of skepticism toward the left; at the age of 20, he wrote that "the right of property is absolute."[10] Peter Gay describes Taine's reaction to the Jacobins as stigmatization, drawing on The French Revolution,[11][12] in which Taine argues:

Some of the workmen are shrewd Politicians whose sole object is to furnish the public with words instead of things; others, ordinary scribblers of abstractions, or even ignoramuses, and unable to distinguish words from things, imagine that they are framing laws by stringing together a lot of phrases.[13]

This reaction led Taine to reject the French Constitution of 1793 as a Jacobin document, dishonestly presented to the French people.[14] Taine rejected the principles of the Revolution[15][16] in favor of the individualism of his concepts of regionalism and race, to the point that one writer calls him one of "the most articulate exponents of both French nationalism and conservatism."[17][18]

Other writers, however, have argued that, though Taine displayed increasing conservatism throughout his career, he also formulated an alternative to rationalist liberalism that was influential for the social policies of the Third Republic.[19] Taine's complex politics have remained hard to read; though admired by liberals like Anatole France, he has been the object of considerable disdain in the twentieth century, with a few historians working to revive his reputation.[20]

Taine is best known now for his attempt at a scientific account of literature, based on the categories of race, milieu, and moment.[21][22] Taine used these words in French (race, milieu et moment); the terms have become widespread in literary criticism in English, but are used in this context in senses closer to the French meanings of the words than the English meanings, which are, roughly, "nation", "environment" or "situation", and "time".[23][24]

Taine argued that literature was largely the product of the author's environment, and that an analysis of that environment could yield a perfect understanding of the work of literature. In this sense he was a sociological positivist (see Auguste Comte),[25] though with important differences. Taine did not mean race in the specific sense now common, but rather the collective cultural dispositions that govern everyone without their knowledge or consent. What differentiates individuals within this collective "race", for Taine, was milieu: the particular circumstances that distorted or developed the dispositions of a particular person. The "moment" is the accumulated experiences of that person, which Taine often expressed as momentum; to some later critics, however, Taine's conception of moment seemed to have more in common with Zeitgeist.[26]

Though Taine coined and popularized the phrase "race, milieu, et moment," the theory itself has roots in earlier attempts to understand the aesthetic object as a social product rather than a spontaneous creation of genius. Taine seems to have drawn heavily on the philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder's ideas of volk (people) and nation in his own concept of race;[27] the Spanish writer Emilia Pardo Bazán has suggested that a crucial predecessor to Taine's idea was the work of Germaine de Staël on the relationship between art and society.[28]

تشکر نظر شما نمی تواند ارسال شود

گزارش کردن نظر

گزارش ارسال شد

گزارش شما نمی تواند ارسال شود

بررسی خود را بنویسید

نظر ارسال شد

نظر شما نمی تواند ارسال شود

check_circle

check_circle