- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : جهت برخورداری از تخفیف سایت ثبت نام و با کد کاربری خود سفارش ثبت نمائید. زیرا تخفیف فقط برای اعضا در نظر گرفته شده و قابل رویت است.

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 100000 ریال باشد .

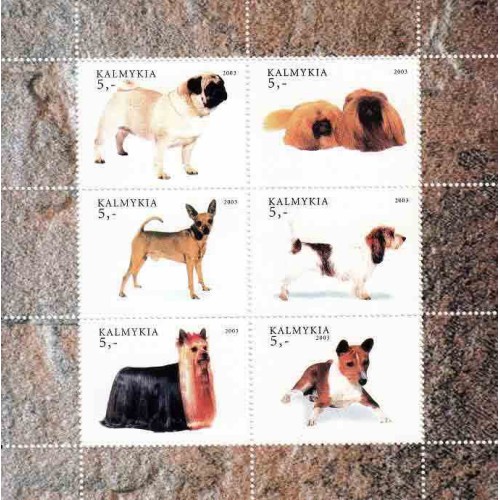

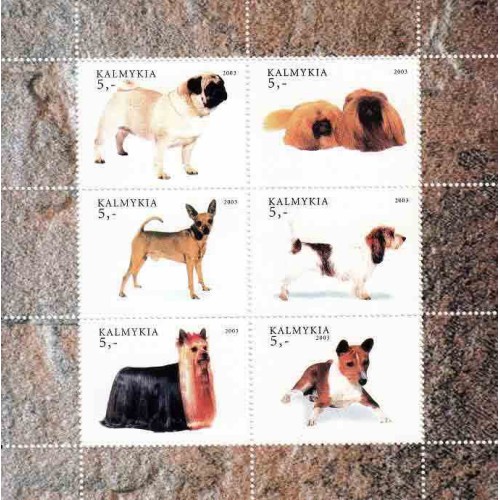

قالموقستان (Хальмг Таңһч )(به روسی: Респу́блика Калмы́кия) یکی از جمهوریهای روسیه است. پایتخت آن شهر الیستا و جمعیت آن ۲۸۹٬۴۸۱ نفر است. (سال ۲۰۱۰). دین ۳۷.۶ درصد از مردم این ناحیه بودایی است. [۱]

این جمهوری در زبان اویغوری قالماقیستان نامیده میشود.

| جمهوری قالموقستان قالموقستانХальмг Таңһч روسیРеспублика Калмыкия | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| جمهوری | |||

|

|||

| Anthem: سرود ملی قالموقستان | |||

جایگاه جمهوری قالموقستان بر روی نقشه فدراسیون روسیه |

|||

| مختصات: ۴۶°۳۴′ شمالی ۴۵°۱۹′ شرقیمختصات: ۴۶°۳۴′ شمالی ۴۵°۱۹′ شرقی | |||

| کشور | |||

| منطقه فدرالی | جنوبی | ||

| منطقه اقتصادی | ولگا | ||

| بزرگترین شهر | الیستا | ||

| تاسیس | ۹ ژانویه ۱۹۵۷ | ||

| مرکز | الیستا | ||

| دولت | |||

| • Type | جمهوری | ||

| • رئیس جمهور نخست وزیر |

آلکسی اورلوف ندارد |

||

| مساحت | |||

| • جمهوری |

۷۶٬۱۰۰ km۲ (۲۹٬۰۰۰ sq mi)

|

||

| رتبه منطقه | ۴۱ ام | ||

| جمعیت (۲۰۱۰) | |||

| • جمهوری | ۲۸۹٬۴۸۱ | ||

| • رتبه | ۷۸ام | ||

| • تراکم |

۳٫۸/km۲ (۹٫۹/sq mi)

|

||

| • شهری | ٪۴۴٫۳ | ||

| • روستایی | ٪۵۵٫۷ | ||

| نژاد | |||

| • قالموقستان روسی بقیه |

٪۵۳٫۳ ۳۳٫۶٪ ۱۱٫۱٪ |

||

| کد ایزو ۳۱۶۶ | RU-KL | ||

| پلاک خودرو | ۰۸ | ||

| زبان های رسمی | روسی ، قالموقی | ||

| واحد پول | روبل | ||

The Republic of Kalmykia (Russian: Респу́блика Калмы́кия, tr. Respublika Kalmykiya; IPA: [rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə kɐlˈmɨkʲɪjə]; Kalmyk: Хальмг Таңһч, Hal'mg Tanghch) is a federal subject of Russia (a republic). As of the 2010 Census, its population was 289,481.[9]

It is the only region in Europe where Buddhism is the plurality religion.[15] It has become well known as an international center for chess because its former President, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, is the head of the International Chess Federation (FIDE).

The republic is located in the southwestern part of European Russia and borders, clockwise, with Volgograd Oblast in the northwest and north, Astrakhan Oblast in the north and east, the Republic of Dagestan in the south, Stavropol Krai in the southwest, and with Rostov Oblast in the west. It is washed by the Caspian Sea in the southeast.

A small stretch of the Volga River flows through eastern Kalmykia. Other major rivers include the Yegorlyk, the Kuma, and the Manych. Lake Manych-Gudilo is the largest lake; other lakes of significance include Lakes Sarpa and Tsagan-Khak. In all, however, Kalmykia possesses few lakes.

Kalmykia's natural resources include coal, oil, and natural gas.

The republic's wildlife includes the saiga antelope, whose habitat is protected in Chyornye Zemli Nature Reserve.

Kalmykia has a continental climate, with very hot and dry summers and cold winters with little snow. The average January temperature is −5 °C (23 °F) and the average July temperature is +24 °C (75 °F). Average annual precipitation ranges from 170 millimeters (6.7 in) in the east of the republic to 400 millimeters (16 in) in the west.

According to the Kurgan Hypothesis the upland regions of Kalmykia formed part of the cradle of Indo-European culture. Hundreds of Kurgans can be seen in these areas.

The territory of Kalmykia is unique in that it has been the home in successive periods to many major world religions and ideologies. Prehistoric paganism and heathendom (shamanism) gave way to Judaism with the Khazars. This was succeeded by Islam with the Alans while the Mongol hordes brought Tengriism, and the later Nogais were Moslem, before their replacement by the present-day Buddhist Oirats/Kalmyks. With the annexation of the territory by the Russian Empire, Christianity arrived with Slavic settlers, while all religions were suppressed after the Russian Revolution, when Communism dominated. Shamanism has in all probability remained a constant, often hidden, substrate of folk-practice, as it is today.

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (November 2007) |

The ancestors of the Kalmyks, the Oirats, migrated from the steppes of southern Siberia on the banks of the Irtysh River to the Lower Volga region. Various reasons have been given for the move, but the generally accepted answer is that the Kalmyks sought abundant pastures for their herds. Another motivation may have been to escape the growing dominance of the neighboring Dzungar Mongol tribe.[16] They reached the lower Volga region in or about 1630. That land, however, was not uncontested pastures, but rather the homeland of the Nogai Horde, a confederation of Turkic-speaking nomadic tribes. The Kalmyks expelled the Nogais who fled to the Caucasian plains and to the Crimean Khanate, areas under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Some Nogai groups sought the protection of the Russian garrison at Astrakhan. The remaining nomadic Mongol Oirats tribes became vassals of Kalmyk Khan.

The Kalmyks settled in the wide open steppes from Saratov in the north to Astrakhan on the Volga delta in the south and to the Terek River in the southwest. They also encamped on both sides of the Volga River, from the Don River in the west to the Ural River in the east. Although these territories had been recently annexed by Russia, it was in no position to settle the area with Russian colonists. This area under Kalmyk control would eventually be called the Kalmyk Khanate.

Within twenty-five years of settling in the lower Volga region, the Kalmyks became subjects of the Tsar. In exchange for protecting Russia’s southern border, the Kalmyks were promised an annual allowance and access to the markets of Russian border settlements. The open access to Russian markets was supposed to discourage mutual raiding on the part of the Kalmyks and of the Russians and Bashkirs, a Russian-dominated Turkic people, but this was not often the practice. In addition, Kalmyk allegiance was often nominal, as the Kalmyk Khans practiced self-government, based on a set of laws they called the Great Code of the Nomads (Iki Tsaadzhin Bichig).

The Kalmyk Khanate reached its peak of military and political power under Ayuka Khan (1669–1724). During his era, the Kalmyk Khanate fulfilled its responsibility to protect the southern borders of Russia and conducted many military expeditions against its Turkic-speaking neighbors. Successful military expeditions were also conducted in the Caucasus. The Khanate experienced economic prosperity from free trade with Russian border towns, China, Tibet and with their Muslim neighbors. During this era, the Kalmyks also kept close contacts with their Oirat kinsmen in Dzungaria, as well as the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (November 2007) |

After the death of Ayuka Khan, the Tsarist government implemented policies that gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies, for instance, encouraged the establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures the Kalmyks roamed in the lower Volga region. The settlers took over land used by Kalmyks to feed their livestock and, in some cases, forced Kalmyks into servitude. The Russian Orthodox church, by contrast, pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. The Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, diluting his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. By the mid-18th century, Kalmyks were increasingly disillusioned with Russian encroachment and interference in its internal affairs.

Ubashi Khan, the great-grandson Ayuka Khan and the last Kalmyk Khan, decided to return his people to their ancestral homeland, Dzungaria. Under his leadership, approximately 200,000 Kalmyks migrated directly across the Central Asian desert. Along the way, many Kalmyks were killed in ambushes or captured and enslaved by their Kazakh and Kyrgyz enemies. Many also died of starvation or thirst. After several grueling months of travel, only 96,000 Kalmyks reached the Manchu Empire's western outposts Xinjiang near the Balkhash Lake.

After failing to stop the flight, Catherine the Great abolished the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the Governor of Astrakhan. The Kalmyks who remained in Russian territory continued to fight in Russian wars, e.g., the Napoleonic Wars (1812–1815), the Crimean War (1853–1856) and Ottoman wars. They gradually created fixed settlements with houses and temples, instead of their transportable round felt yurts. In 1865, Elista, the future capital of the Kalmykia, was built. This settlement process lasted until well after the Russian Revolution.

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (November 2007) |

After the October Revolution in 1917, many Don Kalmyks joined the White Russian army and fought under the command of Generals Denikin and Wrangel during the Russian Civil War. Before the Red Army broke through to the Crimean Peninsula towards the end of 1920, a large group of Kalmyks fled from Russia with the remnants of the defeated White Army to the Black Sea ports of Turkey.

The majority of the refugees chose to resettle in Belgrade, Serbia. Other, much smaller, groups chose Sofia (Bulgaria), Prague (Czechoslovakia) and Paris and Lyon (France). The Kalmyk refugees in Belgrade built a Buddhist temple there in 1929.

In the summer of 1919, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin issued an appeal[17] to the Kalmyk people, calling for them to revolt and to aid the Red Army. Lenin promised to provide the Kalmyks, among other things, a sufficient quantity of land for their own use. The promise came to fruition on November 4, 1920 when a resolution was passed by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee proclaiming the formation of the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast. Fifteen years later, on October 22, 1935, the Oblast was elevated to republic status, Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

Contrary to the proclamations of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and of the Bolshevik propaganda slogan promising the "right of nations to self determination," the Oblast and its successor government were not autonomous governing bodies. Its nominal leaders, radical Communist intellectuals, failed to promote and protect the interests of the Kalmyk people, because real power was concentrated in the hands of the Soviet authorities in Moscow. According to Dorzha Arbakov, a Kalmyk school teacher turned anti-Soviet partisan fighter, these governing bodies were a tool the Bolsheviks used to control the Kalmyk people:

... the Soviet authorities were greatly interested in Sovietizing Kalmykia as quickly as possible and with the least amount of bloodshed. Although the Kalmyks alone were not a significant force, the Soviet authorities wished to win popularity in the Asian and Buddhist worlds by demonstrating their evident concern for the Buddhists in Russia.[18]

In spite of the efforts of Soviet authorities to gain popular support, the Kalmyk people remained staunchly loyal, first and foremost to their traditional leaders, the nobility and the clergy, as they always had been. To the Soviet authorities, Kalmykia's leaders were sources of anti-Communism and Kalmyk nationalism. Later on, the authorities would persecute Kalmyk leaders through executions, deportations to labor camps in Siberia and the confiscation of property.

After establishing control, the Soviet authorities did not overtly enforce an anti-religion policy, other than through passive means, because it sought to bring Mongolia[19] and Tibet[20] into its sphere of influence. The government also was compelled to respond to domestic disturbances resulting from the economic policies of War Communism and the famine its policies induced in 1921.

The passive measures taken by Soviet authorities to control the people included the imposition of a harsh church tax to close churches, monasteries and parish schools. Public education became mandatory to indoctrinate the youth. The Cyrillic script replaced Todo Bichig, the traditional Kalmyk vertical script. In spite of these measures, some of the better known Kalmyk monasteries were able to expand their religious and educational work.

The Kalmyks of the Don Host, however, were not so fortunate. They were subject to the policies of de-cossackization where villages were destroyed, khuruls (temples) and monasteries were burned down and executions were indiscriminate. At the same time, grain, livestock and other food stuffs were seized. By 1925 the Don Host did not have any khuruls, monasteries or practicing clergy.

In December 1927 the Fifteenth Party Congress of the Soviet Union passed a resolution calling for the "voluntary" collectivization of agriculture, but a shortage of grain in the following year was used as a pretext by the Soviet authorities to use force. The change in policy was accompanied by a new campaign of systematic and merciless repression, directed initially against the small farming class. The objective of this campaign was to suppress the resistance of the farming peasants to full-scale collectivization of agriculture.

In 1931, Joseph Stalin ordered the collectivization, closed the Buddhist monasteries, and burned the Kalmyks' religious texts[citation needed]. He deported all monks and all herdsmen owning more than 500 sheep to Siberia[citation needed]. The forced collectivization (as well as the dry, treeless landscape) was unsuited to the Kalmyk temperament and was a social, economic, and cultural disaster. About 60,000 Kalmyks died during the great famine of 1932 to 1933[citation needed].

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (November 2007) |

On June 22, 1941 the German army invaded the Soviet Union. By August 12, 1942 the German Army Group South captured Elista, the capital of the Kalmyk ASSR. After capturing the Kalmyk territory, German army officials established a propaganda campaign with the assistance of anti-communist Kalmyk nationalists, including white emigre, Kalmyk exiles. The campaign was focused primarily on recruiting and organizing Kalmyk men into anti-Soviet, militia units.

German benevolence, however, did not extend to all people living in the Kalmyk ASSR. At least 93 Jewish families, for example, were rounded up and killed. The total Jewish dead numbered approximately 100.[21]

The Kalmyk units were extremely successful in flushing out and killing Soviet partisans. But by December 1942, the Soviet Red army retook the Kalmyk ASSR, forcing the Kalmyks assigned to those units to flee, in some cases, with their wives and children in hand.

The Kalmyk units retreated westward into unfamiliar territory with the retreating German army and were reorganized into the Kalmuck Legion, although the Kalmyks themselves preferred the name Kalmuck Cavalry Corps. The casualty rate also increased substantially during the retreat, especially among the Kalmyk officers. To replace those killed, the German army imposed forced conscription, taking in teenagers and middle-aged men. As a result, the overall effectiveness of the Kalmyk units declined.

By the end of the war, the remnants of the Kalmuck Cavalry Corps made its way to Austria where the Kalmyk soldiers and their family members became post-war refugees.

Those who did not want to leave formed militia units that chose to stay behind and harass the oncoming Soviet Red Army.

Although a large number of Kalmyks chose to fight against the Soviet Union, the majority by-and-large remained loyal to their country, fighting the German army in regular Soviet Red army units and in partisan resistance units behind the battlelines throughout the Soviet Union. Before their removal from the Soviet Red Army and from partisan resistance units after December 1943, approximately 8,000 Kalmyks were awarded various orders and medals, including 21 Kalmyk men who were recognized as a Hero of the Soviet Union.[22]

On December 27, 1943, Soviet authorities declared the Kalmyk people guilty of cooperation with the German Army and ordered the deportation of the entire Kalmyk population to various locations in Central Asia and Siberia. In conjunction with the deportation, the Kalmyk ASSR was abolished and its territory was split between adjacent Astrakhan, Rostov and Stalingrad Oblasts and Stavropol Krai. To completely obliterate any traces of the Kalmyk people, the Soviet authorities renamed the former republic's towns and villages.[23]

The population transfer occurred immediately in the middle of the evening. No one was given advanced notification or time to assemble their belongings, including warm clothing, in preparation for their forced relocation. They were transported in trucks from their homes to the local railway stations where they were loaded in unheated cattle cars. In many cases, the cars were filled beyond capacity and did not contain bathrooms. Food was not provided, and water fell through the holes and cracks in the cattle car in the form of snow. As a result of these harsh conditions, many children and elderly men and women died en route.

Due to their widespread dispersal in Siberia their language and culture suffered possibly irreversible decline. Khrushchev finally allowed their return in 1957, when they found their homes, jobs and land occupied by imported Russians and Ukrainians, who remained.[citation needed] On January 9, 1957, Kalmykia again became an autonomous oblast, and on July 29, 1958, an autonomous republic within the Russian SFSR.

In the following years bad planning of agricultural and irrigation projects resulted in widespread desertification, and economically unviable industrial plants were constructed.

After dissolution of the USSR, Kalmykia kept the status of an autonomous republic within the newly formed Russian Federation (effective March 31, 1992).