- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 100000 ریال باشد .

توجه : جهت برخورداری از مزایای در نظر گرفته شده برای مشتریان لطفا ثبت نام نمائید.

| Giuseppe Verdi | |

|---|---|

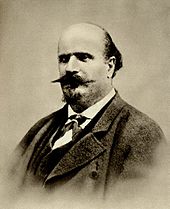

Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi by Giovanni Boldini, 1886

|

|

| Born | Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi 9 or 10 October 1813 Busseto |

| Died | 27 January 1901(1901-01-27) (aged 87) Milan |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe ˈverdi]; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer of operas.

Verdi was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, and developed a musical education with the help of a local patron. Verdi came to dominate the Italian opera scene after the era of Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini, whose works significantly influenced him, becoming one of the pre-eminent opera composers in history.

In his early operas Verdi demonstrated a sympathy with the Risorgimento movement which sought the unification of Italy. He also participated briefly as an elected politician. The chorus "Va, pensiero" from his early opera Nabucco (1842), and similar choruses in later operas, were much in the spirit of the unification movement, and the composer himself became esteemed as a representative of these ideals. An intensely private person, Verdi however did not seek to ingratiate himself with popular movements and as he became professionally successful was able to reduce his operatic workload and sought to establish himself as a landowner in his native region. He surprised the musical world by returning, after his success with the opera Aida (1871), with three late masterpieces: his Requiem (1874), and the operas Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893).

His operas remain extremely popular, especially the three peaks of his 'middle period': Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata, and the bicentenary of his birth in 2013 was widely celebrated in broadcasts and performances.

Verdi, the first child of Carlo Giuseppe Verdi (1785–1867) and Luigia Uttini (1787–1851), was born at their home in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro and within the borders of the First French Empire following the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza in 1808. The baptismal register, prepared on 11 October 1813, lists his parents Carlo and Luigia as "innkeeper" and "spinner" respectively. Additionally, it lists Verdi as being "born yesterday", but since days were often considered to begin at sunset, this could have meant either 9 or 10 October.[1] Verdi himself, following his mother, always celebrated his birthday on 9 October.[2]

Verdi had a younger sister, Giuseppa, who died aged 17 in 1833.[2] From the age of four, Verdi was given private lessons in Latin and Italian by the village schoolmaster, Baistrocchi, and at six he attended the local school. After learning to play the organ, he showed so much interest in music that his parents finally provided him with a spinet.[3] Verdi's gift for music was already apparent by 1820–21 when he began his association with the local church, serving in the choir, acting as an altar boy for a while, and taking organ lessons. After Baistrocchi's death, Verdi, at the age of eight, became the official paid organist.[4]

The music historian Roger Parker points out that both of Verdi's parents "belonged to families of small landowners and traders, certainly not the illiterate peasants from which Verdi later liked to present himself as having emerged... Carlo Verdi was energetic in furthering his son's education...something which Verdi tended to hide in later life... [T]he picture emerges of youthful precocity eagerly nurtured by an ambitious father and of a sustained, sophisticated and elaborate formal education."[5]

In 1823, when he was 10, Verdi's parents arranged for the boy to attend school in Busseto, enrolling him in a Ginnasio—an upper school for boys—run by Don Pietro Seletti, while they continued to run their inn at Le Roncole. Verdi returned to Busseto regularly to play the organ on Sundays, covering the distance of several kilometres on foot.[6] At age 11, Verdi received schooling in Italian, Latin, the humanities, and rhetoric. By the time he was 12, he began lessons with Ferdinando Provesi, maestro di cappella at San Bartolomeo, director of the municipal music school and co-director of the local Società Filarmonica (Philharmonic Society). Verdi later stated: "From the ages of 13 to 18 I wrote a motley assortment of pieces: marches for band by the hundred, perhaps as many little sinfonie that were used in church, in the theatre and at concerts, five or six concertos and sets of variations for pianoforte, which I played myself at concerts, many serenades, cantatas (arias, duets, very many trios) and various pieces of church music, of which I remember only a Stabat Mater."[1] This information comes from the Autobiographical Sketch which Verdi dictated to the publisher Giulio Ricordi late in life, in 1879, and remains the leading source for his early life and career.[7] Written, understandably, with the benefit of hindsight, it is not always reliable when dealing with issues more contentious than those of his childhood.[8][9]

The other director of the Philharmonic Society was Antonio Barezzi, a wholesale grocer and distiller, who was described by a contemporary as a "manic dilettante" of music. The young Verdi did not immediately become involved with the Philharmonic. By June 1827, he had graduated with honours from the Ginnasio and was able to focus solely on music under Provesi. By chance, when he was 13, Verdi was asked to step in as a replacement to play in what became his first public event in his home town; he was an immediate success mostly playing his own music to the surprise of many and receiving strong local recognition.[10]

By 1829–30, Verdi had established himself as a leader of the Philharmonic: "none of us could rival him" reported the secretary of the organisation, Giuseppe Demaldè. An eight-movement cantata, I deliri di Saul, based on a drama by Vittorio Alfieri, was written by Verdi when he was 15 and performed in Bergamo. It was acclaimed by both Demaldè and Barezzi, who commented: "He shows a vivid imagination, a philosophical outlook, and sound judgment in the arrangement of instrumental parts."[11] In late 1829, Verdi had completed his studies with Provesi, who declared that he had no more to teach him.[12] At the time, Verdi had been giving singing and piano lessons to Barezzi's daughter Margherita; by 1831, they were unofficially engaged.[1]

Verdi set his sights on Milan, then the cultural capital of northern Italy, where he applied unsuccessfully to study at the Conservatory.[1] Barezzi made arrangements for him to become a private pupil of Vincenzo Lavigna, who had been maestro concertatore at La Scala, and who described Verdi's compositions as "very promising."[13] Lavigna encouraged Verdi to take out a subscription to La Scala, where he heard Maria Malibran in operas by Gioachino Rossini and Vincenzo Bellini.[14] Verdi began making connections in the Milanese world of music that were to stand him in good stead. These included an introduction by Lavigna to an amateur choral group, the Società Filarmonica, led by Pietro Massini.[15] Attending the Società frequently in 1834, Verdi soon found himself functioning as rehearsal director (for Rossini's La cenerentola) and continuo player. It was Massini who encouraged him to write his first opera, originally titled Rocester, to a libretto by the journalist Antonio Piazza.[1]

In mid-1834, Verdi sought to acquire Provesi's former post in Busseto but without success. But with Barezzi's help he did obtain the secular post of maestro di musica. He taught, gave lessons, and conducted the Philharmonic for several months before returning to Milan in early 1835.[5] By the following July, he obtained his certification from Lavigna.[16] Eventually in 1835 Verdi became director of the Busseto school with a three-year contract. He married Margherita in May 1836, and by March 1837, she had given birth to their first child, Virginia Maria Luigia on 26 March 1837. Icilio Romano followed on 11 July 1838. Both the children died young, Virginia on 12 August 1838, Ilicio on 22 October 1839.[1]

In 1837, the young composer asked for Massini's assistance to stage his opera in Milan.[17] The La Scala impresario, Bartolomeo Merelli, agreed to put on Oberto (as the reworked opera was now called, with a libretto rewritten by Temistocle Solera)[18] in November 1839. It achieved a respectable 13 additional performances, following which Merelli offered Verdi a contract for three more works.[19]

While Verdi was working on his second opera Un giorno di regno, Margherita died of encephalitis at the age of 26. Verdi adored his wife and children and was devastated by their deaths. Un giorno, a comedy, was premiered only a few months later. It was a flop and only given the one performance.[19] Following its failure, it is claimed Verdi vowed never to compose again,[9] but in his Sketch he recounts how Merelli persuaded him to write a new opera.

Verdi was to claim that he gradually began to work on the music for Nabucco, the libretto of which had originally been rejected by the composer Otto Nicolai:[20] "This verse today, tomorrow that, here a note, there a whole phrase, and little by little the opera was written", he later recalled.[21] By the autumn of 1841 it was complete, originally under the title Nabucodonosor. Well received at its first performance on 9 March 1842, Nabucco underpinned Verdi's success until his retirement from the theatre, twenty-nine operas (including some revised and updated versions) later.[9] At its revival in La Scala for the 1842 autumn season it was given an unprecedented (and later unequalled) total of 57 performances; within three years it had reached (among other venues) Vienna, Lisbon, Barcelona, Berlin, Paris and Hamburg; in 1848 it was heard in New York, in 1850 in Buenos Aires. Porter comments that "similar accounts...could be provided to show how widely and rapidly all [Verdi's] other successful operas were disseminated."[22]

A period of hard work for Verdi—with the creation of twenty operas (excluding revisions and translations)—followed over the next sixteen years, culminating in Un ballo in maschera. This period was not without its frustrations and setbacks for the young composer, and he was frequently demoralised. In April 1845, in connection with I due Foscari, he wrote: "I am happy, no matter what reception it gets, and I am utterly indifferent to everything. I cannot wait for these next three years to pass. I have to write six operas, then addio to everything."[23] In 1858 Verdi complained: "Since Nabucco, you may say, I have never had one hour of peace. Sixteen years in the galleys."[24]

After the initial success of Nabucco, Verdi settled in Milan, making a number of influential acquaintances. He attended the Salotto Maffei, Countess Clara Maffei's salons in Milan, becoming her lifelong friend and correspondent.[9] A revival of Nabucco followed in 1842 at La Scala where it received a run of fifty-seven performances,[25] and this led to a commission from Merelli for a new opera for the 1843 season. I Lombardi alla prima crociata was based on a libretto by Solera and premiered in February 1843. Inevitably, comparisons were made with Nabucco; but one contemporary writer noted: "If [Nabucco] created this young man's reputation, I Lombardi served to confirm it."[26]

Verdi paid close attention to his financial contracts, making sure he was appropriately remunerated as his popularity increased. For I Lombardi and Ernani (1844) in Venice he was paid 12,000 lire (including supervision of the productions); Attila and Macbeth (1847), each brought him 18,000 lire. His contracts with the publishers Ricordi in 1847 were very specific about the amounts he was to receive for new works, first productions, musical arrangements, and so on.[27] He began to use his growing prosperity to invest in land near his birthplace. In 1844 he purchased Il Pulgaro, 62 acres (23 hectares) of farmland with a farmhouse and outbuildings, providing a home for his parents from May 1844. Later that year, he also bought the Palazzo Cavalli (now known as the Palazzo Orlandi) on the via Roma, Busseto's main street.[28] In May 1848, Verdi signed a contract for land and houses at Sant'Agata in Busseto, which had once belonged to his family.[29] It was here he built his own house, completed in 1880, now known as the Villa Verdi, where he lived from 1851 until his death.[30]

In March 1843, Verdi visited Vienna (where Gaetano Donizetti was musical director) to oversee a production of Nabucco. The older composer, recognising Verdi's talent, noted in a letter of January 1844: "I am very, very happy to give way to people of talent like Verdi... Nothing will prevent the good Verdi from soon reaching one of the most honourable positions in the cohort of composers."[31] Verdi travelled on to Parma, where the Teatro Regio di Parma was producing Nabucco with Strepponi in the cast. For Verdi the performances were a personal triumph in his native region, especially as his father, Carlo, attended the first performance. Verdi remained in Parma for some weeks beyond his intended departure date. This fuelled speculation that the delay was due to Verdi's interest in Giuseppina Strepponi (who stated that their relationship began in 1843).[32] Strepponi was in fact known for her amorous relationships (and many illegitimate children) and her history was an awkward factor in their relationship until they eventually agreed on marriage.[33]

After successful stagings of Nabucco in Venice (with twenty-five performances in the 1842/43 season), Verdi began negotiations with the impresario of La Fenice to stage I Lombardi, and to write a new opera. Eventually, Victor Hugo's Hernani was chosen, with Francesco Maria Piave as librettist. Ernani was successfully premiered in 1844, and within six months had been performed at twenty other theatres in Italy, and also in Vienna.[34] The writer Andrew Porter notes that for the next ten years, Verdi's life "reads like a travel diary – a timetable of visits...to bring new operas to the stage or to supervise local premieres." La Scala premiered none of these new works, except for Giovanna d'Arco. Verdi "never forgave the Milanese for their reception of Un giorno di regno."[27]

During this period, Verdi began to work more consistently with his librettists. He relied on Piave again for I due Foscari, performed in Rome in November 1844, then on Solera once more for Giovanna d'Arco, at La Scala in February 1845, while in August that year he was able to work with Salvadore Cammarano on Alzira for the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Solera and Piave worked together on Attila for La Fenice (March 1846).[35]

In April 1844, Verdi took on Emanuele Muzio, eight years his junior, as a pupil and amanuensis. He had known him since about 1828 as another of Barezzi's protégés.[36] Muzio, who in fact was Verdi's only pupil, became indispensable to the composer. He reported to Barezzi that Verdi "has a breadth of spirit, of generosity, a wisdom."[37] In November 1846, Muzio wrote of Verdi: "If you could see us, I seem more like a friend, rather than his pupil. We are always together at dinner, in the cafes, when we play cards...; all in all, he doesn't go anywhere without me at his side; in the house we have a big table and we both write there together, and so I always have his advice."[38] Muzio was to remain associated with Verdi, assisting in the preparation of scores and transcriptions, and later conducting many of his works in their premiere performances in the USA and elsewhere outside Italy. He was chosen by Verdi as one of the executors of his will, but predeceased the composer in 1890.[39]

After a period of illness Verdi began work on Macbeth in September 1846. He dedicated the opera to Barezzi: "I have long intended to dedicate an opera to you, as you have been a father, a benefactor and a friend for me. It was a duty I should have fulfilled sooner if imperious circumstances had not prevented me. Now, I send you Macbeth, which I prize above all my other operas, and therefore deem worthier to present to you."[40] In 1997 Martin Chusid wrote that Macbeth was the only one of Verdi's operas of his "early period" to remain regularly in the international repertoire,[41] although in the 21st century Nabucco has also entered the lists.[42]

Strepponi's voice declined and her engagements dried up in the 1845 to 1846 period, and she returned to live in Milan whilst retaining contact with Verdi as his "supporter, promoter, unofficial adviser, and occasional secretary" until she decided to move to Paris in October 1846. Before she left Verdi gave her a letter that pledged his love. On the envelope, Strepponi wrote: "5 or 6 October 1846. They shall lay this letter on my heart when they bury me."[43]

Verdi had completed I masnadieri for London by May 1847 except for the orchestration. This he left until the opera was in rehearsal, since he wanted to hear "la [Jenny] Lind and modify her role to suit her more exactly."[44] Verdi agreed to conduct the premiere on 22 July 1847 at Her Majesty's Theatre, as well as the second performance. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert attended the first performance, and for the most part, the press was generous in its praise.[45]

For the next two years, except for two visits to Italy during periods of political unrest, Verdi was based in Paris.[46] Within a week of returning to Paris in July 1847, he received his first commission from the Paris Opéra. Verdi agreed to adapt I Lombardi to a new French libretto; the result was Jérusalem, which contained significant changes to the music and structure of the work (including an extensive ballet scene) to meet Parisian expectations.[47] Verdi was awarded the Order of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour.[48][n 1] To satisfy his contracts with the publisher Francesco Lucca, Verdi dashed off Il Corsaro. Budden comments "In no other opera of his does Verdi appear to have taken so little interest before it was staged."[51]

On hearing the news of the "Cinque Giornate", the "Five Days" of street fighting that took place between 18 and 22 March 1848 and temporarily drove the Austrians out of Milan, Verdi travelled there, arriving on 5 April.[52] He discovered that Piave was now "Citizen Piave" of the newly proclaimed Republic of San Marco. Writing a patriotic letter to him in Venice, Verdi concluded "Banish every petty municipal idea! We must all extend a fraternal hand, and Italy will yet become the first nation of the world...I am drunk with joy! Imagine that there are no more Germans here!!"[53]

Verdi had been admonished by the poet Giuseppe Giusti for turning away from patriotic subjects, the poet pleading with him to "do what you can to nourish the [sorrow of the Italian people], to strengthen it, and direct it to its goal."[54] Cammarano suggested adapting Joseph Méry's 1828 play La Bataille de Toulouse, which he described as a story "that should stir every man with an Italian soul in his breast".[55] The premiere was set for late January 1849. Verdi travelled to Rome before the end of 1848. He found that city on the verge of becoming a (short-lived) republic, which commenced within days of La battaglia di Legnano's enthusiastically received premiere. In the spirit of the time were the tenor hero's final words, "Whoever dies for the fatherland cannot be evil-minded".[56]

Verdi had intended to return to Italy in early 1848, but was prevented by work and illness, as well as, most probably, by his increasing attachment to Strepponi. Verdi and Strepponi left Paris in July 1849, the immediate cause being an outbreak of cholera,[57] and Verdi went directly to Busseto to continue work on completing his latest opera, Luisa Miller, for a production in Naples later in the year.[58]

Verdi was committed to the publisher Giovanni Ricordi for an opera—which became Stiffelio—for Trieste in the Spring of 1850; and, subsequently, following negotiations with La Fenice, developed a libretto with Piave and wrote the music for Rigoletto (based on Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse) for Venice in March 1851. This was the first of a sequence of three operas (followed by Il trovatore and La traviata) which were to cement his fame as a master of opera.[59] The failure of Stiffelio (attributable not least to the censors of the time taking offence at the taboo subject of the supposed adultery of a clergyman's wife and interfering with the text and roles) incited Verdi to take pains to rework it, although even in the completely recycled version of Aroldo (1857) it still failed to please.[60]Rigoletto, with its intended murder of royalty, and its sordid attributes, also upset the censors. Verdi would not compromise:

What does the sack matter to the police? Are they worried about the effect it will produce?...Do they think they know better than I?...I see the hero has been made no longer ugly and hunchbacked!! Why? A singing hunchback...why not?...I think it splendid to show this character as outwardly deformed and ridiculous, and inwardly passionate and full of love. I chose the subject for these very qualities...if they are removed I can no longer set it to music.[61]

Verdi substituted a Duke for the King, and the public response and subsequent success of the opera all over Italy and Europe fully vindicated the composer.[62] Aware that the melody of the Duke's song "La donna è mobile" ("Woman is fickle") would become a popular hit, Verdi excluded it from orchestral rehearsals for the opera, and rehearsed the tenor separately.[63][n 2]

For several months Verdi was preoccupied with family matters. These stemmed from the way in which the citizens of Busseto were treating Giuseppina Strepponi, with whom he was living openly in an unmarried relationship. She was shunned in the town and at church, and while Verdi appeared indifferent, she was certainly not.[65] Furthermore, Verdi was concerned about the administration of his newly acquired property at Sant'Agata.[66] A growing estrangement between Verdi and his parents was perhaps also attributable to Strepponi[67] (The suggestion that this situation was sparked by the birth of a child to Verdi and Strepponi which was given away as a foundling[68] lacks any firm evidence). In January 1851, Verdi broke off relations with his parents, and in April they were ordered to leave Sant'Agata; Verdi found new premises for them and helped them financially to settle into their new home. It may not be coincidental that all six Verdi operas written in the period 1849–53 (La battaglia, Luisa Miller, Stiffelio, Rigoletto, Il trovatore and La traviata), have, uniquely in his oeuvre, heroines who are, in the opera critic Joseph Kerman's words, "women who come to grief because of sexual transgression, actual or perceived". Kerman, like the psychologist Gerald Mendelssohn, sees this choice of subjects as being influenced by Verdi's uneasy passion for Strepponi.[69]

Verdi and Strepponi moved into Sant'Agata on 1 May 1851.[70] May also brought an offer for a new opera from La Fenice, which Verdi eventually realised as La traviata. That was followed by an agreement with the Rome Opera company to present Il trovatore for January 1853.[71] Verdi now had sufficient earnings to retire, should he have wished to do so.[72] He had reached a stage where he could develop his operas as he wished, rather than be dependent on commissions from third parties. Il trovatore was in fact the first opera he wrote without a specific commission (apart from Oberto).[73] At around the same time he began to consider creating an opera from Shakespeare's King Lear. After first (1850) seeking a libretto from Cammarano (which never appeared), Verdi later (1857) commissioned one from Antonio Somma, but this proved intractable, and no music was ever written.[74][n 3] Verdi began work on Il trovatore after the death of his mother in June 1851. The fact that this is "the one opera of Verdi's which focuses on a mother rather than a father" is perhaps related to her death.[77]

In the winter of 1851–52 Verdi decided to go to Paris with Strepponi where he concluded an agreement with the Opéra to write what became Les vêpres siciliennes, his first original work in the style of grand opera. In February 1852, the couple attended a performance of Alexander Dumas fils's play, The Lady of the Camellias; Verdi immediately began to compose music for what would later become La traviata.[78]

After his visit to Rome for Il trovatore in January 1853, Verdi worked on completing La traviata, but with little hope of its success, due to his lack of confidence in any of the singers engaged for the season.[79] Furthermore, the management insisted that the opera be given a historical, not a contemporary setting. The premiere in March 1853 was indeed a failure: Verdi wrote: "Was the fault mine or the singers'? Time will tell."[80] Subsequent productions (following some rewriting) throughout Europe over the following two years fully vindicated the composer; Roger Parker has written "Il trovatore consistently remains one of the three or four most popular operas in the Verdian repertoire: but it has never pleased the critics".[81]

In the eleven years up to and including Traviata, Verdi had written sixteen operas. Over the next eighteen years (up to Aida), he wrote only six new works for the stage.[82] Verdi was happy to return to Sant'Agata and, in February 1856, was reporting a "total abandonment of music; a little reading; some light occupation with agriculture and horses; that's all". A couple of months later, writing in the same vein to Countess Maffei he stated: "I'm not doing anything. I don't read. I don't write. I walk in the fields from morning to evening, trying to recover, so far without success, from the stomach trouble caused me by I vespri siciliani. Cursed operas!"[83] An 1858 letter by Strepponi to the publisher Léon Escudier describes the kind of lifestyle that increasingly appealed to the composer: "His love for the country has become a mania, madness, rage, and fury—anything you like that is exaggerated. He gets up almost with the dawn, to go and examine the wheat, the maize, the vines, etc....Fortunately our tastes for this sort of life coincide, except in the matter of sunrise, which he likes to see up and dressed, and I from my bed."[84]

Nonetheless on 15 May, Verdi signed a contract with La Fenice for an opera for the following spring. This was to be Simon Boccanegra. The couple stayed in Paris until January 1857 to deal with these proposals, and also the offer to stage the translated version of Il trovatore as a grand opera. Verdi and Strepponi travelled to Venice in March for the premiere of Simon Boccanegra, which turned out to be "a fiasco" (as Verdi reported, although on the second and third nights, the reception improved considerably).[85]

With Strepponi, Verdi went to Naples early in January 1858 to work with Somma on the libretto of the opera Gustave III, which over a year later would become Un ballo in maschera. By this time, Verdi had begun to write about Strepponi as "my wife" and she was signing her letters as "Giuseppina Verdi".[84] Verdi raged against the stringent requirements of the Neapolitan censor stating: "I'm drowning in a sea of troubles. It's almost certain that the censors will forbid our libretto."[86] With no hope of seeing his Gustavo III staged as written, he broke his contract. This resulted in litigation and counter-litigation; with the legal issues resolved, Verdi was free to present the libretto and musical outline of Gustave III to the Rome Opera. There, the censors demanded further changes; at this point, the opera took the title Un ballo in maschera.[87]

Arriving in Sant'Agata in March 1859 Verdi and Strepponi found the nearby city of Piacenza occupied by about 6,000 Austrian troops who had made it their base, to combat the rise of Italian interest in unification in the Piedmont region. In the ensuing Second Italian War of Independence the Austrians abandoned the region and began to leave Lombardy, although they remained in control of the Venice region under the terms of the armistice signed at Villafranca. Verdi was disgusted at this outcome: "[W]here then is the independence of Italy, so long hoped for and promised?...Venice is not Italian? After so many victories, what an outcome... It is enough to drive one mad" he wrote to Clara Maffei.[88]

Verdi and Strepponi now decided on marriage; they travelled to Collonges-sous-Salève, a village then part of Piedmont. On 29 August 1859 the couple were married there, with only the coachman who had driven them there and the church bell-ringer as witnesses.[89] At the end of 1859, Verdi wrote to his friend Cesare De Sanctis "[Since completing Ballo] I have not made any more music, I have not seen any more music, I have not thought anymore about music. I don't even know what colour my last opera is, and I almost don't remember it." [90] He began to remodel Sant'Agata, which took most of 1860 to complete and on which he continued to work for the next twenty years. This included major work on a square room that became his workroom, his bedroom, and his office.[91]