- جدید

- ناموجود

توجه : درج کد پستی و شماره تلفن همراه و ثابت جهت ارسال مرسوله الزامیست .

توجه:حداقل ارزش بسته سفارش شده بدون هزینه پستی می بایست 100000 ریال باشد .

توجه : جهت برخورداری از مزایای در نظر گرفته شده برای مشتریان لطفا ثبت نام نمائید.

|

|

This article does not cite any sources. (December 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

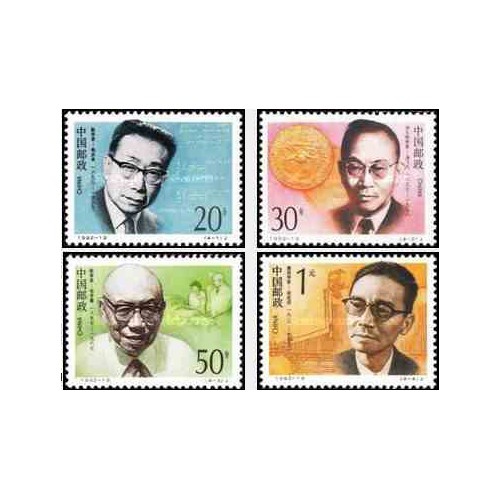

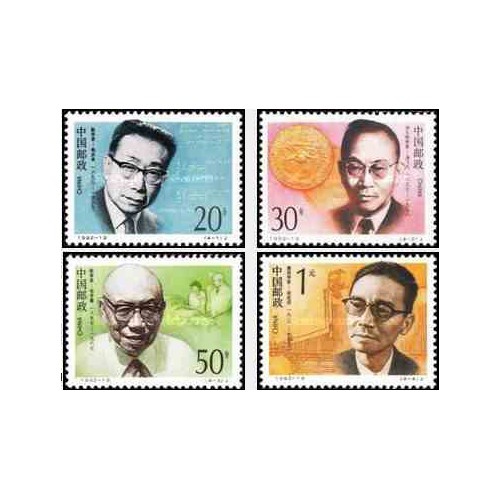

Xiong Qinglai, or Hiong King-Lai (simplified Chinese: 熊庆来; traditional Chinese: 熊慶來; pinyin: Xióng Qìnglái; Wade–Giles: Hsiung Ch'ing-lai, October 20, 1893 – February 3, 1969), courtesy name Dizhi (迪之), was a Chinese mathematician from Yunnan. He was the first person to introduce modern mathematics into China, and served as an influential president of Yunnan University from 1937 through 1947. A Chinese stamp was issued in his honour.

Xiong studied in Europe for eight years (1913 to 1921) before returning to China to teach. During that time, Chinese university-level mathematics was only comparable to Western secondary-school mathematics level. In 1921, he established the Department of Mathematics of National Southeastern University (Later renamed National Central University and Nanjing University), beginning undertook the task of writing more than ten textbooks on geometry, calculus, differential equations, mechanics, etc. It was the first endeavor in history to introduce modern mathematics in Chinese textbooks. In 1926, Xiong became a professor of mathematics at Tsinghua University, where he influenced the path of Hua Luogeng, who later became another prominent mathematician.

Xiong was persecuted to death in 1969 during the Cultural Revolution.

| Tang Fei-fan | |

|---|---|

Tang Fei-fan in 1944 in Kunming, Yunnan.

|

|

| Native name | 湯飛凡 (Tāng Fēifán) |

| Born | July 23, 1897 Liling, Hunan, Qing Empire |

| Died | September 30, 1958 (aged 61) Beijing, People's Republic of China Suicide |

| Other names | Tang Ruizhao (湯瑞昭) |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Fields | Medical microbiology |

| Institutions | Central Epidemic Prevention Laboratory |

| Education | Chengnan School |

| Alma mater | Xiangya College of Medicine Yale University Peking Union Medical College Harvard University |

| Doctoral advisor | Hans Zinsser |

| Known for | Chlamydia trachomatis |

| Influences | Hans Zinsser |

| Spouse | He Lian (何璉) (m. 1925–58) (Tang Fei-fan died in 1958.) |

Tang Fei-fan (simplified Chinese: 汤飞凡; traditional Chinese: 湯飛凡; pinyin: Tāng Fēifán; July 23, 1897 - September 30, 1958) was a Chinese medical microbiologist best known for culturing the Chlamydia trachomatis agent in the yolk sacs of eggs.[1][2]

During the "Pulling Out Bourgeois White Flag Movement", Tang was brought to be persecuted and suffered political persecution in 1957, he fully demonstrated the attitude not to compromise with the Communist Party at all by suicide to end his own life.

Tang was born Tang Ruizhao (湯瑞昭) in Tangjiaping Village of Liling, Hunan, on July 23, 1897, to a relatively poor gentry family, during the Qing Empire.[3] He was the second of three children. He had a younger brother, Tang Qiufan (湯秋凡).[3] His father Tang Luquan (湯麓泉) taught at a family friend He Zhongshan's (何忠善) old-style private school, in which Tang Fei-fan studied poetry, history, philosophy, mathematics, and natural science. He's son, He Jian, became Tang Fei-fan's close friend.[3] "Learning from the West with its advanced science and technology;Invigorating the Chinese nation", Tang Fei-fan had often heard the hometown folks talk about reform and revolution in his childhood. When the Chinese were called "sick man of Asia", Tang fei-fan determined to study medicine science.[3]

At the age of twelve, he attended Chengnan School in Changsha, capital of Hunan province.[3] After graduating from the Xiangya College of Medicine (now Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University) in 1921, he earned his doctor's degree in medical science from Yale University.[3] He went back to China in 1921 and that year studied, then taught at Peking Union Medical College.[3] In 1925 he went to the United States again to study bacteriology under Professor Hans Zinsser at Harvard University.[4] He returned to China in 1929 and in the meantime became professor at Medical School of National Central University.[4] In 1935 he was recruited as a researcher at the British National Institute for Medical Research, a position in which he remained until 1937.[3][4] One day, a Japanese visitor want to shake hands with Tang Fei-fan, he refused and sternly said: "My motherland is being invaded by you country. It's a pity that I can't shake hands with you, please ask your country to stop the invasion of my motherland!"[3]

After the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1938, he founded the Central Epidemic Prevention Laboratory in Kunming, capital of southwest China's Yunnan province, and served as its director.[3][4] He made China's first batch of penicillin vaccines and serum with his team for the soldiers at the front.[4] After war he established China's first antibiotic research and penicillin production workshop, as well as normal BCG vaccine laboratory.[4]

In 1947 he paid a fact-finding visit to the United Kingdom, attended the 4th World Conference of International Union of Microbiological Societies (IUMS) in the Kingdom of Denmark, and became its standing committee.[4]

After the establishment of the Communist State, Tang successively served as director of Institute of Biological Products of the Ministry of Health, director of Chinese Medical Association, and director general of Chinese Society for Microbiology.[3] In 1950 he joined the newly created National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products, working as its director.[3] During his time in office, he directed to develop China's first biological products specification - Verification Regulation of Biological Products (《生物製品檢定規程(草案)》).[3] That same year, a terrible plague hit the whole north China, he developed China's own yellow fever vaccine.[3]

In the mid 1950s, he first cultured the Chlamydia trachomatis agent in the yolk sacs of eggs.

In 1958, the "Pulling Out Bourgeois White Flag Movement" (拔资产阶级白旗运动) broke out.[3] Tang was denounced and labeled as "capitalist academic authority", "scum of the nation", "a faithful running dog for the Kuomintang reactionaries", "American spy", "International spy", "a large white flag on the socialist positions", "ride on the backs of the people", "pseudo scientist", "sell the interests of his own country".[3] Because of the unbearable insult he killed himself on September 30, 1958.[3][5]

In 1978, the Communist Party rehabilitated many victims who suffered political persecution or died in the mass socialism political movements except Tang Fei-fan. In June 1979, the Ministry of Health held a memorial service for him.

In 1981, the I/O Acceleration Technology (IOAT) bestowed its gold medal upon him.[3] But the foreign scholars didn't know that he had died. He was held in high esteem by British sinologist Joseph Needham.[3]

| Liang Sicheng | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Liang at Tsinghua University, 1950

|

|||

| Born | 20 April 1901 Tokyo, Japan |

||

| Died | 9 January 1972 (aged 70) Beijing, China |

||

| Alma mater | Tsinghua University University of Pennsylvania |

||

| Political party | Communist Party of China | ||

| Spouse(s) | Lin Huiyin Lin Zhu |

||

| Children | Liang Congjie Liang Zaibing |

||

| Parent(s) | Liang Qichao | ||

| Chinese name | |||

| Chinese | 梁思成 | ||

|

|||

Liang Sicheng (Chinese: 梁思成; 20 April 1901[1] – 9 January 1972) was a Chinese architect and scholar often known as the "father" of modern Chinese architecture. His father, Liang Qichao, was one of the most prominent Chinese scholars of the early 20th century. His wife was the architect and poet Lin Huiyin. His younger brother, Liang Siyong, was one of China's first archaeologists.

Liang is the author of China's first modern history on Chinese architecture and founder of the Architecture Department of Northeastern University in 1928 and Tsinghua University in 1946. He was the Chinese representative in the Design Board which designed the United Nations headquarters in New York City. He, along with Lin Huiyin, Mo Zongjiang (1916–1999), and Ji Yutang (1902–c. 1960s), discovered and analyzed the first and second oldest timber structures still standing in China, located at Nanchan Temple and Foguang Temple at Mount Wutai.

He is recognized as the “Father of Modern Chinese Architecture”. To cite Princeton University, which awarded him an honorary doctoral degree in 1947, he was “a creative architect who has also been a teacher of architectural history, a pioneer in historical research and exploration in Chinese architecture and planning, and a leader in the restoration and preservation of the priceless monuments of his country.”

Liang Sicheng was born on April 20, 1901 in Tokyo, Japan, where his father Liang Qichao was in exile from China after the failed Hundred Days' Reform. During the waning years of the Qing Dynasty, China’s last Imperial dynasty, the empire endured a series of foreign invasions and vicious domestic struggles, beginning with the first Opium War in 1840. Foreign powers soon divided China into spheres of influence, while the weak and corrupt Qing Dynasty could do little to stop them. In 1898 the Guangxu Emperor, led by his circle of advisers, attempted to introduce drastic reforms to stem the decay and bring China onto the path to modernity. Liang Qichao, a well-educated and energetic man, was a leader of this movement. However, in the face of opposition from conservatives in the Qing court, the movement failed. The Empress Dowager Cixi, the emperor's adoptive mother and the power behind the throne, imprisoned the emperor, and executed many of the movement's leaders. Liang Qichao took refuge in Japan, where his eldest son was born.

After the Qing Dynasty was overthrown in 1911, Liang Qichao, Liang Sicheng's father, returned to China from his exile in Japan. He briefly served in the government of the newly established Republic, which was unfortunately taken over by a faction of warlords in Northern China (the "Beiyang" clique, meaning Northern Ocean). Liang Qichao quit his government post and initiated a social and literary movement to introduce modern, Western thought to Chinese society.

Liang Sicheng was educated by his father in this progressive environment. In 1915, Liang entered Tsinghua College, a preparatory school in Beijing. (This college later became Tsinghua University, now among the best universities in China.) In 1924, he and Lin went to University of Pennsylvania funded by Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Scholarship to study architecture under Paul Cret. Three years later, Liang received his master's degree in architecture. He greatly benefited from his education in America, which also prepared him for his future career as a scholar and professor in China.

In 1928, Liang married Lin Huiyin (known in the United States as Phyllis Lin), who was an equally renowned scholar in modern China. She was recognized as an artist, architect and poet, admired by and friend with several famous scholars of her time, such as poet Xu Zhimo (whom she also had a brief relationship with), philosopher Jin Yuelin and economist Chen Daisun.

When the couple went back in 1928, they were invited by the Northeastern University in Shenyang. At that time Shenyang was under the control of Japanese troops, which was a big challenge to perform any professional practice. They went anyway, established the second School of Architecture in China, but also the first curriculum which took a western one (to be precise the curriculum from University of Pennsylvania) as its prototype. Their effort was interrupted by Japan’s occupation in the following year, but after 18 years, in 1946, the Liangs were again able to practice their professorship in Tsinghua University in Beijing. This time a more systematic and all-around curriculum was discreetly put forward, consisted of courses of fine arts, theory, history, science, and professional practice. This has become a reference for any other school of architecture later developed in China. This improvement also reflected the change of architectural style from the Beaux-Arts tradition to the modernist Bauhaus style since the 1920s.

In 1930, Liang and his colleague, Zhang Rui, won an award of the physical plan of Tianjin. This plan incorporates the contemporary American techniques in zoning, public administration, government finance and municipal engineering. Liang's involvement in city planning was further inspired by Clarence Stein, the chairman of the Regional Planning Association of America. They met in Beiping in 1936 during Stein's trip to Asia. Liang and Stein became good friends and in Liang's visit to the US in 1946/7, Liang stayed in Stein's apartment when he came to New York City. Stein played an instrumental role in the establishment of the architectural and planning program at Tsinghua University.[2]

In 1931, Liang became a member of a newly developed organization in Beijing called the Society for Research in Chinese Architecture. He felt a strong impulse to study Chinese traditional architecture and that it was his responsibility to interpret and convey its building methods. It was not an easy task. Since the carpenters were generally illiterate, methods of construction were usually conveyed orally from master to apprentice, and were regarded as secrets within every craft. In spite of these difficulties, Liang started his research by "decoding" classical manuals and consulting the workmen who have the traditional skills.

From the start of his new career as a historian, Liang was determined to search and discover what he termed the “grammar” of Chinese architecture. He recognized that throughout China’s history the timber-frame had been the fundamental form of construction. He also realized that it was far from enough just to sit in his office day and night engaged in the books. He had to get out searching for the surviving buildings in order to verify his assumptions. His first travel was in April 1932. In the following years he and his colleagues successively discovered some survived traditional buildings, including: the Foguang Temple (857), the Temple of Solitary Joy (984), the Yingzhou Pagoda (1056), Zhaozhou Bridge (589-617), and many others. Because of their effort, these buildings managed to survive.

Following the Mukden Incident in 1931, Imperial Japan began establishing strangleholds throughout China's north, ultimately culminating into a full-scale war generally known as War of Resistance (a culmination of the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War 2, 1937–45), which forced Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin to cut short their cultural restoration work in Beijing, and flee southward along with faculty and materials of the Architectural Department of Northeastern University. Liang and Lin along with their children and their university continued their studies and research work in temporary settlements in the cities of Tianjin, Kunming, and finally in Lizhuang. During the later stages of WWII, the Americans began heavy bombing of the Japanese homeland.[3] Liang, whose brother-in-law Lin Heng served as a fighter pilot in the air force and died in the air war against Japan, recommended that the Americans military authorities to spare the ancient Japanese cities of Kyoto and Nara: "architecture is the epitome of society and the symbol of the people. But it does not belong to one people, for it is the crystallization of the entire human race. Nara's Toshodaiji Temple is the world's earliest wood-structure building. Once destroyed, it is irrecoverable." The U.S. military accepted Liang’s proposal. As a result, even though Japan was heavily bombed, Nara remained intact with its original scenery unaffected by the war.[4][5]

After the war, Liang was invited to establish the architectural and urban planning programs at Tsinghua University. In 1946, he went to Yale University as a visiting fellow and served as the Chinese representative in the design of the United Nations Headquarters Building. In 1947, Liang received an honorary doctoral degree from Princeton University. He visited major architectural programs and influential architects in order to develop a model program at Tsinghua before returning China.

To spread and share his understandings and appreciation of Chinese architecture, and most importantly, to help save its diminishing building technologies, Liang published his first book, Qing Structural Regulations in 1934. The book was on the study of the methods and rules of Qing architecture with the 1734 Qing Architecture Regulation and several other ancient manuals as the textbook, the carpenters as teachers, and the Forbidden City in Beijing as teaching material. Since its publication, for more than seven decades, this book has become a standard textbook for anyone who wants to understand the essence of ancient Chinese architecture. Liang considered the study of Qing Structural Regulation as a stepping stone to the much more daunting task of studying the Song dynasty Yingzao Fashi (Treatise on Architectural Methods), due to the large number of specialist terms used in that manual differing substantially from the Qing dynasty architectural terminology.

Liang's study of Yingzao Fashi spanned more than two decades, from 1940 to 1963, and the first draft of his Annotated Yingzao Fashi was completed in 1963.[6] However, due to the eruption of the Cultural Revolution in China, the publication of this work was cut short. Liang's Annotated Yingzao Fashi was published posthumously by Tsinghua University Architecture Department's Yingzao Fashi Study Group in 1980. (The text occupies all of Volume 7 in his ten-volume Collected Works).

Liang considered the Yingzao Fashi and Qing Structural Regulations as "two grammar books of Chinese architecture." He wrote, "both government manuals, they are of the greatest importance for the study of the technological aspects of Chinese architecture."[7]

Another book, History of Chinese Architecture,[8] was "the first thing of its kind." In his words, this book was "an attempt to organize the materials collected by myself and other members of the Institute during the past twelve years." He had divided the previous 3,500 years into six architectural periods, defined each period by references to historical and literary citations, described existing monuments of each period, and finally analyzed the architecture of each period as evidenced from a combination of painstaking library and field research. All of these books became the platform for later scholars to explore the principles and evolution of Chinese architecture, and are still considered classics today.

Liang's posthumous manuscript "Chinese Architecture, A Pictorial History", written in English, edited by Wilma Fairbank (费慰梅) was published by MIT Press in 1984 and won ForeWord Magazine's Architecture "Book of the Year" Award".[9]